The Comparative Script System – Part 7

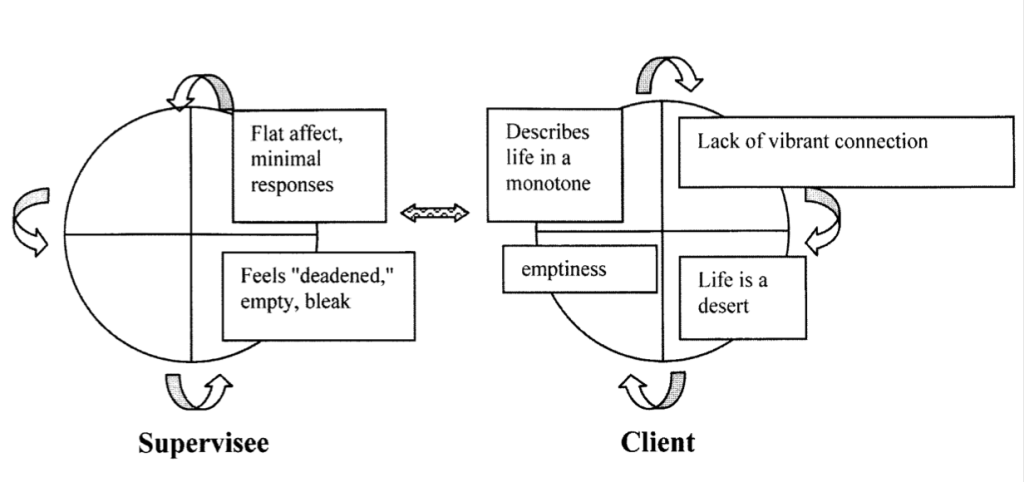

Isa began to talk about Kanda’s early life. He was the only child of a unsupported mother who suffered from serious postnatal depression. His earliest remembered experience was of endless silent days alone with her in a gloomy room, from which he could see the other children in the street. Mother would sit silently and motionless for hours, only stirring from her seat to make something for his supper, then returning again to her chair or to her bed. Kanda passed the time staring at the patterns on the fading wallpaper. This was Kanda’s earliest experience (Section A). His impression of the environment and of himself was of a heavy, depressed desert (Section B). He brought it with him throughout his life and reproduced it in his relationships (C). Kanda’s behavior in the consulting room was somewhat withdrawn, with flat affect (Section D), and his therapist felt correspondingly low and flat when she was with him, almost as if she were becoming the depressed mother. She also found it hard to be interested in him. There was a danger that the early relationship would be repeated (Section A).

Although later in his life Kanda had developed many other ways of being, which could be mapped on the script system, his most fundamental “layer” was of this unconscious, preverbal experience. The supervisor invited Isa to sit and listen to the group as they shared their own feelings, sensations, and images that had been evoked by Kanda’s story. Gradually, Isa began to feel enlivened. She felt a huge grief for Kanda and realized that she knew that she could carry this with her to the consulting room.

Her own sections A and B were, of course, still blank. But she began to share with her colleagues a little of her own history with an ill mother. She cried and knew that she had a good deal to take to her therapist (Figure 8).

Figure 8

An “Implicit” Relational Pattern

H2>Conclusion

Used as a framework for gathering data, the comparative script system can be a highly useful tool for theory integration, assessment, and treatment planning. In addition, it can be a map to highlight the relational field for in-depth exploration. But as Korzybski (1933) famously said, “The map is not the territory.” The work of being willing to explore the cocreated field takes place within the self, not outside in a picture. The comparative script system provides the frame or container for the work, holding the process as the supervisee explores. It accounts for the unconscious processes of both participants in the therapeutic relationship while respecting the boundary of the supervisee’s personal therapy. Finally, in our opinion, the use of the comparative script system can support and help the development of a specific transactional analytic theory and practice of supervision, one capable of integrating several different aspects of our theoretical frame of reference in a coherent and effective system.

Charlotte Sills, M.A., M.Sc. (psychotherapy), is a Teaching and Supervising Transactional Analyst (psychotherapy), a member of EATA and the ITAA, and a visiting professor at Middlesex University. She works in private practice in London, United Kingdom, and is a tutor and supervisor at Metanoia Institute, London, and Ashridge College, UK. She can be reached at 2, Richmond Road, London W5 5NS, UK; e-mail: contact@charlottesills.co.uk.

Marco Mazzetti, M.D., is a psychiatrist, a Teaching and Supervising Transactional Analyst (psychotherapy), a member of EATA and the ITAA, and a university lecturer. He carries out his clinical, training, and research activities at the Centro di Psicologia e Analisi Transazionale and at the Ethno-Psychiatry Service Terrenuove of Milan, Italy. He can be reached at Centro di Psicologia e Analisi Transazionale, Via Archimede, 127, 20129 Milan, Italy; e-mail: marcomazzetti.at@libero.it .

REFERENCES

Berne, E. (1961). Transactional analysis in psychotherapy: An systematic individual and social psychiatry.

New York: Grove Press.

Bollas, C. (1987). The shadow of the object: Psychoanalysis of the unthought known. New York: Columbia University Press.

Clarkson, P. (1992). Transactional analysis psychotherapy: An integrated approach. London: Routledge. Erskine, R. G. (1982). Supervision for psychotherapy: Models for professional development. Transactional Analysis Journal, 12, 314-321.

Korzybski, A. (1933). Science and sanity: An introduction to non-Aristotelian systems and general semantics. Chicago: Institute of General Semantics.

Lapworth, P., Sills, C., & Fish, S. (2001). Integration in counselling and psychotherapy: Finding a personal approach. London: Sage.

Mazzetti, M. (2007). Supervision in transactional analysis: An operational model. Transactional Analysis Journal, 37, 93-103.

Sills, C. (1985). Developmental stages of the psychotherapy trainee. Supervision course presented at Metanoia Institute, London.

Sills, C., & Salters, D. (1991). The comparative script system. ITA News, 31, 1-15.

Ware, P. (1983). Personality adaptations (doors to therapy). Transactional Analysis Journal, 13, 11-19.