The Comparative Script System – Part 5

This post is a continuation of Charlotte Sills’ and Marco Mazzetti’s article on The Comparative Script System. If you’re just joining us, you might want to start at Part One.

The Comparative Script System in Practice

Case One: The Very Beginner. Niccolò is a young colleague who has just started training.  The supervisor has the privilege of offering him his first supervision a couple of days after his first therapy session with his first client: an absolute beginner!

The supervisor has the privilege of offering him his first supervision a couple of days after his first therapy session with his first client: an absolute beginner!

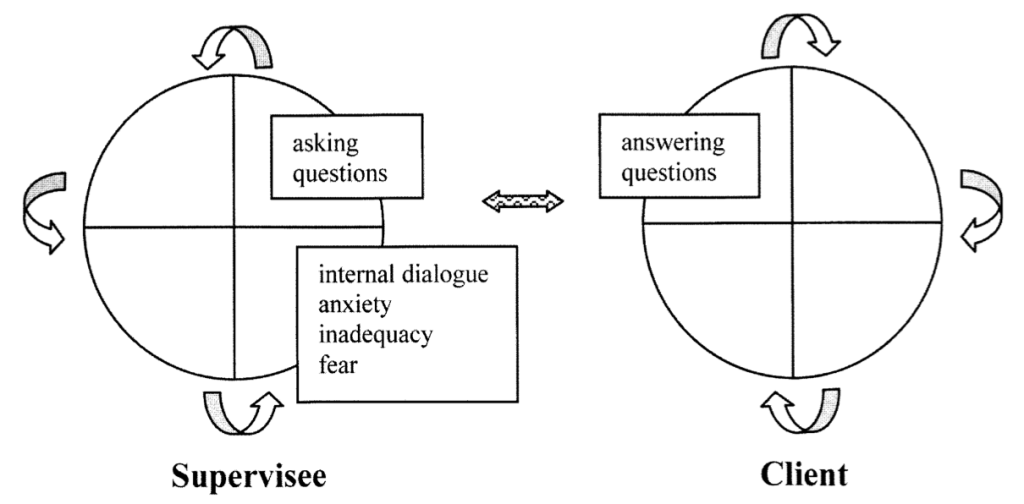

In the training group, Niccolò starts to speak about that session; after 20 minutes, and in spite of several questions from his peers, the only information the group and the supervisor gleaned about the client was that he was a man, aged between 20 and 70, living in a village. On the other hand, they learned a good deal about Niccolò’s subjective experience during the session: he was very anxious, scared of not helping the patient, with a strong internal critical dialogue. The supervisor drew two circles, filling them with all the data collected by that point. They had substantial information about section C (internal experiences) and D (behavior) in the therapist’s circle, a little about section D (behavior) in the client’s circle, and almost nothing else. The main internal experiences of the therapist were anxiety, inadequacy, fear of being a poor therapist, and insecurity. He reported asking many questions, but he could not recall the answers (Section D). The client’s behavior was to answer the questions.

As shown in Figure 5, several sections remained without information, and the relational field (represented by the small double-headed arrow) looked very weak. This picture is not unusual at the beginning stages of practice, when trainees are often most focused on non countertransferential internal experiences. In other words, they are preoccupied with their internal dialogue and their need to grapple with a new role (Erskine, 1982; Mazzetti, 2007; Sills, 1985).

Drawing the circles helped the trainee to become aware of his internal experiences and of how they were overwhelming the relational field and the encounter with the client. At this point, the supervisor invited him to become curious about the man who had come to his office, and Niccolò, for the first time during the supervision session, really focused on his client. He discovered that he knew a good deal about him: he was 61 years old, recently retired, and had moved from a big town to his village of origin where, over the past few years, during weekends and holidays, he had founded and run a small music school as part of the town’s cultural center. After retirement, he had been hoping to work full time in the association, but the new town council had withdrawn funding for his activities.

Figure 5

Niccolò’s First Therapeutic Encounter

As he talked, Niccolò understood that his client was very sad about this and possibly also depressed as a result of losing, at the same time, both his job and his cultural activity. He felt moved by this man. Then the supervisor asked the trainee if he liked music: “Yes, very much. Before university I was at the music high school, and I play the piano well!” “So, you have a lot of things to talk about together!” The supervision ended positively, and Niccolò looked forward to the next session with his client.

Thus, the comparative script system helped this trainee to focus on the relationship with the client and to move away from his own internal dialogue. At the same time, he was aware of the implications of the left part of his circle (section A and B), which was still blank. He began to connect what happened during the therapy session with his past patterns and decided to talk about it with his own therapist.

Case Two: Trainee Supervisors. Sofia and Alice are two experienced trainees and members of a Provisional Teaching and Supervising Transactional Analyst (PTSTA) training group. Both are skilled therapists and good supervisors, and they are comfortable using the comparative script system. Within the training group, they have peer supervision, with Alice bringing a case and Sofia acting as supervisor.

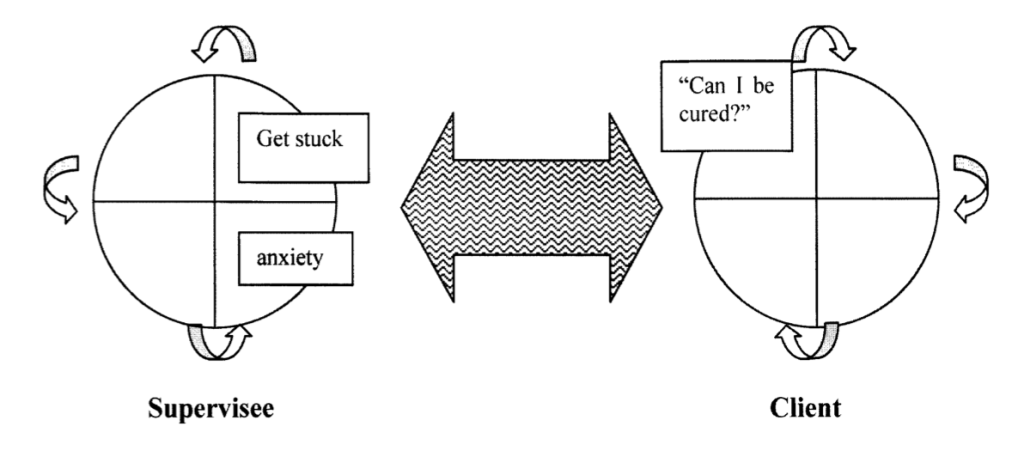

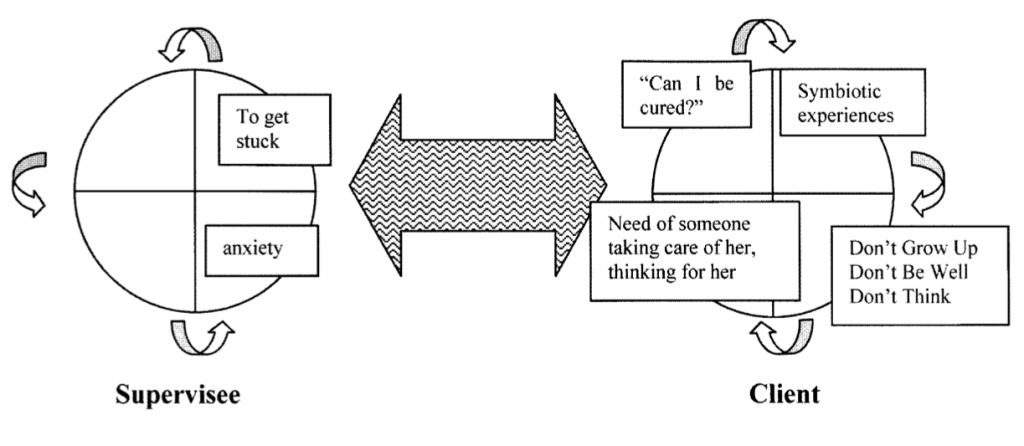

Alice begins: “I want to understand what happened during the session I had with a new client, a 20-year-old girl with a serious eating disorder. As soon as she said, ‘Doctor, do you think I can be cured?’ I felt strong anxiety and I got stuck.”

Sofia drew the circles. She asked about the client’s behavior, then about Alice’s internal experience of anxiety and her stuck behavior, which was to ask many closed, unnecessary questions about the client’s situation. It was evident that the relational field was intense and how aware of it Alice was (Figure 6).

Figure 6

An Intense and Overwhelming Relational Field

Carefully, the two colleagues conducted an inquiry to complete the client’s script system. With the supervisor’s help, Alice thought about what lay behind her client’s question. She understood the life of dependency that the client lived, based on the information she had about the first and second-order symbiosis that had been established with her mother in infancy and that had continued since (Section A). She reflected on the lack of boundaries in her client’s family and conceptualized the probable main injunctions and early decisions of the young woman’s script (B). Alice could hypothesize about the client’s current internal experience: probably a strong need for someone to take care of her, think for her, and take responsibility for her (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Considering the Client’s Script