The Comparative Script System – Part 4

This post is a continuation of Charlotte Sills’ and Marco Mazzetti’s article on The Comparative Script System. If you’re just joining us, you might want to start at Part One.

This post is a continuation of Charlotte Sills’ and Marco Mazzetti’s article on The Comparative Script System. If you’re just joining us, you might want to start at Part One.

Other Uses of the Model

The comparative script system can also be used to think about different therapeutic approaches or interventions. Many, or even most, psychotherapists and counselors give clients the opportunity to “tell their story” (Section A). Focusing on Section B, the therapist may emphasize identifying script beliefs and challenging assumptions. Or, in Section C, working within the transference, the therapist might help clients to become aware of their “unthought known” (Bollas, 1987)—unconscious relational patterns—as they emerge in the relational space between them. Or the therapist may decide to stay tightly in the present, challenging discounts as they emerge in redefining transactions and passive behaviors. And so on.

The Comparative Script System in Supervision

We now introduce a development of the comparative script system that addresses the three major supervisory challenges we described earlier in this article.

Identifying Key Issues. First, the model can be used in supervision—or in self-supervision —as an instrument for identifying the client’s key issues (Clarkson, 1992; Mazzetti, 2007). Supervisor and supervisee can draw the model and, with appropriate inquiry, gradually fill in the sections (representing the areas of the client’s psyche and life), paying attention to where there are gaps and raising questions about possible unexplored avenues. This can be helpful in clarifying assessment and case overview.

According to supervisees’ particular approaches, they will choose to focus more on some sections than on others, but they are likely to notice that their work naturally takes them from one section to another and back again as they follow the client’s process. If a therapist and client become “stuck,” it may be helpful to use Ware’s (1983) “doors to therapy” to identify the client’s accessibility in different sections. Alternatively, the therapist may simply experiment with intervening at the level of behavior, narrative, assumptions, or here-and-now thinking/ feeling to discover which is most useful to the client at that point.

The model also helps to identify key issues for the supervisee’s professional development. Using it with several clients, a therapist might discover a previously unidentified area for his or her own development, such as recognizing that he or she has an unnecessary bias toward working in a particular section while neglecting another. Especially in long-term training (e.g., in preparing a trainee for Certified Transactional Analysis exams), the supervisor can use this tool to help the supervisee to become aware of such biases and developmental directions.

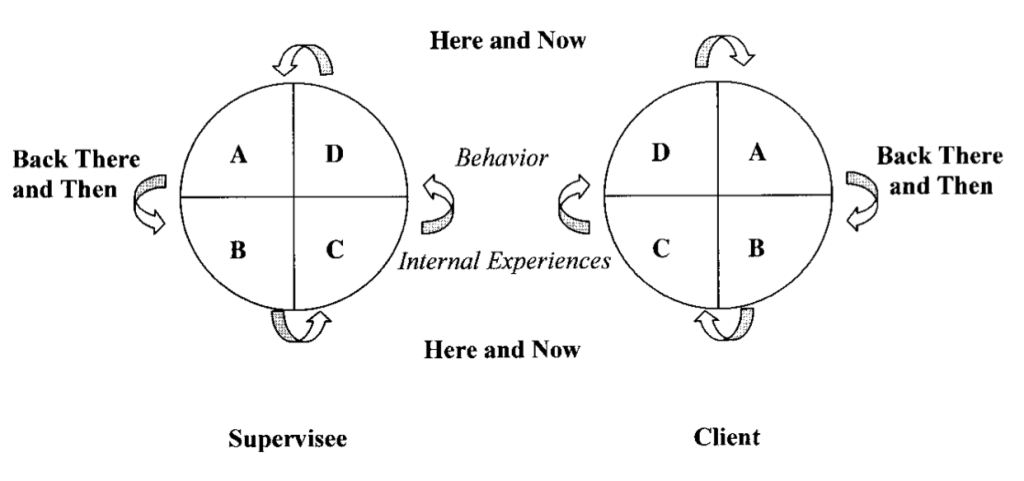

Understanding the Relational Field. The comparative script system can also be useful in describing the relational field between supervisees and their clients by representing the interplay of cocreated dynamics as well as the habitual patterns of each participant. Figure 3 shows two cycles, one representing the client and the other the supervisee. Both individuals have their “there-and-then” sections and a present-centered part in which they exchange their actual experiences.

It should be noted that, for the purposes of two-dimensional illustration, two adjustments are made. First, the system has been rotated so that there are now two vertical halves. Second, the circle on the left, which represents the supervisee’s process, has been flipped so the two circles are now mirror images.

During supervision, as just described, we can help supervisees to fill the four sections of the client circle and, with appropriate questions, the right-hand side (sections C and D) of their own circle as a way to help them become aware of their relevant internal experiences during the session, their behaviors, and the way in which these are related to the internal experiences and behaviors of the client. The left section of the supervisee remains blank.

Figure 3

Mapping the Field of Therapy

Recognizing the Professional Boundary. The left section of the supervisee’s circle is very relevant, however, and the supervisor must be sensitive in dealing with it. Because it refers to the personal issues of the therapist—to his or her past experiences and possible script apparatus —the supervisor needs to respect the boundary between therapy and supervision by avoiding addressing it directly. At the same time, it is vital not to discount it; in fact, its relevance to the therapist’s experience must be brought into awareness. Only in this way can the subtleties of cocreated enactment be appreciated and utilized in the therapy.

By drawing the left part of the diagram, the supervisor is accounting for it; by leaving it blank, the supervisor is modeling respect for its boundary.

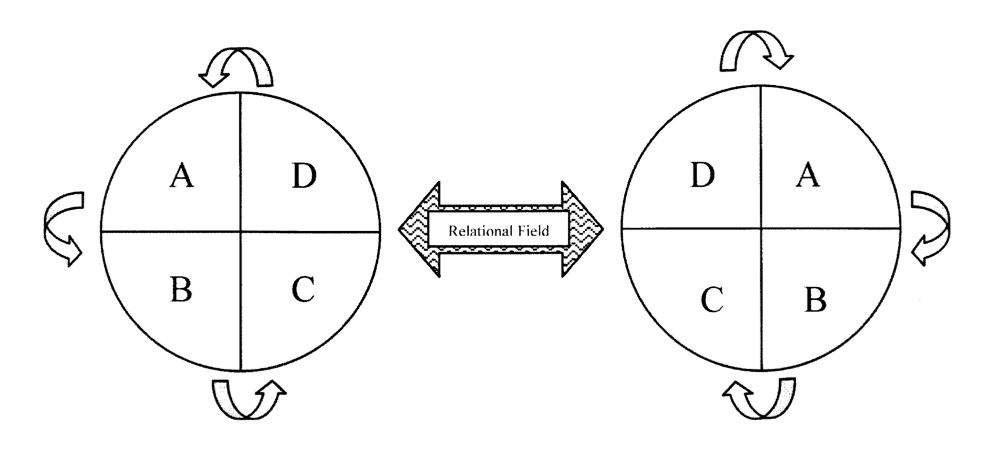

Figure 4

The Relational Field

In Figure 4 the relational field is drawn as a bilateral vector (the double-headed arrow), the size of which varies to symbolize the intensity and impact of the transference-countertransference dynamics.