The Comparative Script System – Part 3

This post is a continuation of Charlotte Sills’ and Marco Mazzetti’s article on The Comparative Script System. If you’re just joining us, you might want to start at Part One.

This post is a continuation of Charlotte Sills’ and Marco Mazzetti’s article on The Comparative Script System. If you’re just joining us, you might want to start at Part One.

The Cycle in Action: Some Examples. This model is actually a learning cycle. It can be either positive or negative.

For instance, a child, Ben, is taught to read sitting on his father’s knee as they look at the pictures together and spell out the words. Father is a man who revels in reading and discovery, and he delights in his son’s pleasure at learning. Ben’s experience is of feeling clever and loved and stimulated (Section A: the early experience). He comes to “know” that learning is fun and rewarding and that his beloved parent encourages and supports him (B). When later at his nursery school he is faced with the book table covered in many new and colorful books, he feels excited and expects to understand them. He also expects support from the teacher: the current “parent figure” (C). He reads and enjoys himself, asking for help when he needs it and reveling in his competence. As an adolescent and later an adult, this pattern continues. He reads copiously and integrates his reading into his work as a teacher, trying out theories and techniques (D). He has thus regularly brought about a repetition of his experience in Section A.

Although this system is self-reinforcing by its nature, it is not a closed system. This means that individuals can assimilate new information and, therefore, constantly update their beliefs (Section B) in light of new experiences. For example, after several attempts at an engineering manual, Ben decides that not all learning is exciting or pleasurable for him, and he chooses to further his study of English literature. This capacity for updating is a sign of healthy learning. Thus, beliefs about self, others, and the world, found in Section B, are changed or modified, leading to a change in patterns of internal response (C) and new behavior (D), which creates new experiences in A.

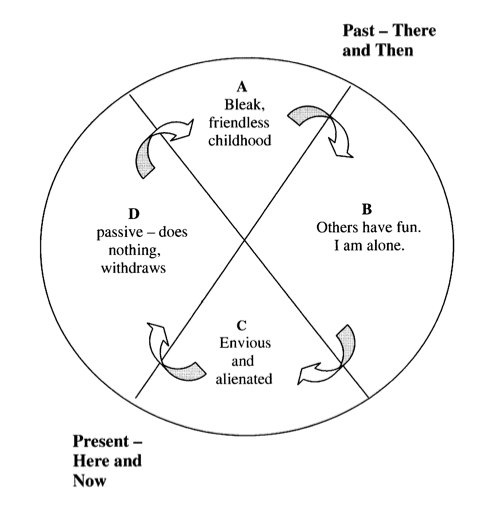

However, as transactional analysts, we may need to focus on the pathological elements of a person’s learning and how her or his script system of thinking, feeling, and behaving becomes a closed one that binds energy and limits new learning and options. This happens when the responses of the environment are inadequate or inappropriate to the child’s needs. For example, Kanda’s mother did not allow him to play in the street with the other children, and he remembers sitting at his window and watching them play football or tag (Section A). He recalls thinking, “Other people have all the fun—nothing exciting ever happens to me” (Section B). Later, at school, when he was invited by the teacher to audition for the school play, he felt depressed and resigned, believing he would never have a chance to get a part (Section C). Consequently, he did not attend the auditions (D) and ended up watching the other children enjoy the rehearsals (A) and thinking, “Other people have all the fun” (B). As an adult, Kanda spends his leisure hours reading the newspaper and watching television. He is frequently envious of the people he reads about and sees and of his friends, who seem to have much more exciting lives (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Kanda’s Script System

To reiterate, the early experience in Section A involves the interplay between the environment and the child’s feelings, sensations, and needs. How these are managed has a major effect on whether experiences can be integrated in a healthy way into a realistic frame of reference. When the feelings or bodily affective experience is repressed, either because the child experiences it as impossible to contain or as a reaction to the nonvalidating or negative response of the environment, there is a higher likelihood of the person developing a closed system.