The Comparative Script System – Part 2

This post is a continuation of Charlotte Sills’ and Marco Mazzetti’s article on The Comparative Script System. If you’re just joining us, you might want to start at Part One.

This post is a continuation of Charlotte Sills’ and Marco Mazzetti’s article on The Comparative Script System. If you’re just joining us, you might want to start at Part One.

The Comparative Script System

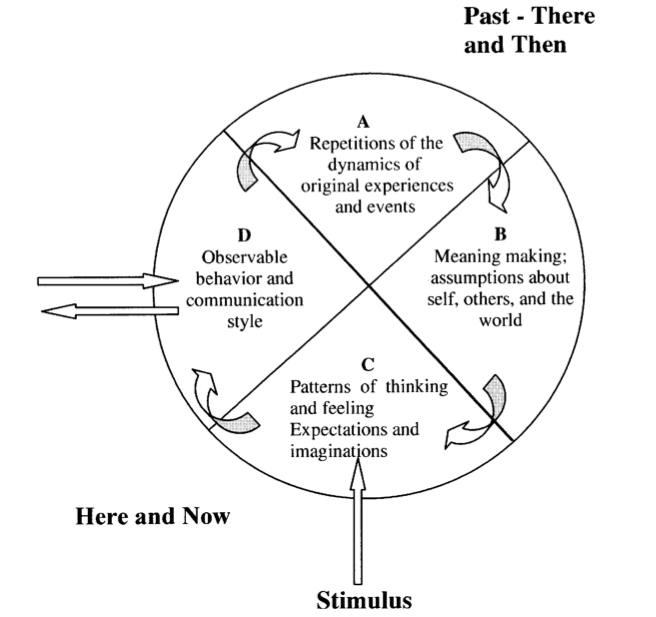

The comparative script system model is essentially a dynamic map that describes how human beings—from childhood onward—develop their personalities and learn to be in the world. It is a visual model, and while we need many words to go through it in prose, the reader can look at Figure 1 and see immediately how it works. It is predicated on the fact that human beings are meaning-making creatures. We make sense of the experiences that result from an interplay of our needs, feelings, and desires in relationship with a more or less responsive world. And the sense we make may be conscious, cognitive sense or it may be unconscious protocol—visceral, emotional, muscular adaptations as we develop our patterns of being in the world with others. Transactional analysis has many way of describing these earliest forms of meaning making: early decisions, relational patterns, organizing principles, script beliefs, life positions, or frame of reference—essentially the “writing” of script. (The “comparative script system” is so called because it is a map of how script is formed, enacted, and maintained. The word “comparative” relates to the model’s first function [Sills & Salters, 1991]: to compare and integrate different theories and schools in transactional analysis.)

As a result of this early meaning making, we humans develop habitual ways of organizing our relationships such that in our current lives we react with feelings, thoughts, and behavior that reinforce and maintain our earliest meaning making. The comparative script system maps this process into a repeating cycle with four sections, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

The Comparative Script System

Section A encompasses the original experiences and repetitions. It represents the early developmental experience of the child: the original protocol and the subsequent palimpsests (Berne, 1961) that are created by culture, family, or chance along with game payoffs that create an echo of the original scene. This section includes the earliest relationships between infant and (m)other and also specific incidents or situations particular to that child’s life.

Section B is the meaning making that emerges if the experiences in A happen often enough or are powerful enough. Sections A and B belong to the past. They represent the writing of script.

Sections C and D describe the here-and-now process. Section C is internal process: the thinking and feeling, sensing and imagining that are habitual responses to current stimuli and events because they emerge from the meaning making. In transactional analysis we speak of discounting, grandiosity, thinking disorders, racket feelings, and transference feelings. Old patterns are particularly intense when a stimulus similar to the one in A is experienced.

Section D, the consequent external manifestation, represents the individual’s behavior based on internal beliefs and processes. The behavior is likely to bring about a repetition of the event in A. Behavior can be analyzed using the drama triangle, transactional analysis “proper,” passive behaviors, and so on. Sections C and D together form the “rackety display” of the racket system. The whole model spells out the unfolding of script, the enactment of a game.