Being There – Part 5

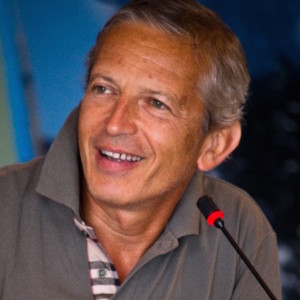

This post is a continuation of Marco Mazzetti’s article ‘Being There’. If you’re just joining us, you might want to start at Part One.

This post is a continuation of Marco Mazzetti’s article ‘Being There’. If you’re just joining us, you might want to start at Part One.

Why Does the Other Person Want (Unconsciously) Me to Feel What I Am Feeling?

This third question is quite often crucial for understanding the meaning of the relational dynamics involved between the client and the practitioner.

Returning to the cases of Edoardo and Linda, we can see the unconscious reasons for their hidden messages and my uncomfortable reactions to them. Edoardo wished to bore me in an attempt to keep me (and probably himself) far away from any possible sexual attraction between us as well as from his inner experiences of shame and his feeling of being wrong and bad. We discovered among his script beliefs the expectation of not being understood and the injunction Don’t Trust/Don’t Be Close. Clearly, he expected to be rejected by me. Gently and respectfully addressing his fear of having someone close was the first step in a successful therapy.

In Linda’s case, she was unconsciously searching for both a new trauma by stimulating my attraction to her and, at the same time, a different, healing experience. The first therapeutic and relational step, after hearing the story of her previous therapy and analyzing the meaning it had for her (Mazzetti, 2010), was to contract clearly for the boundaries of our relationship in order to help her feel safe and reassured. Her possible game con did not find a gimmick. Linda was then able to explore her personal story and identify the script beliefs that had been established, eventually finding new meaning for and a new perspective on her life through a new relational experience.

Conclusion

When I become stuck in supervision, I usually find a solution in the process. I ask myself the three questions I have described here and usually find new options in discovering why the supervisee might be unconsciously stimulating a moment of confusion in me, or a sensation of impotence, or some other difficult perception of myself and the situation.

Usually this is also a useful way to address a parallel process enacted in the supervision session and to open new windows to understanding the dynamics between practitioner and client. Parallel process is one of the most promising and effective tools in supervision because it is evidence of a deep (even if unconscious) knowledge the practitioner has of the client. It is usually easy to become aware of a parallel process through sensitively questioning ourselves about what we are feeling, why we are feeling what we are feeling, and why the other person unconsciously want us to feel that way. Often such complex phenomena as projective identification can be elicited by this procedure.

For this reason, I think that training in developing good contact with ourselves, our feelings and thinking, and their relational implications helps us to become good supervisors and good practitioners as self-supervisors.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

Boyd, S., & Shadbolt, C. (2011). Reflections on a theme of relational supervision. In H. Fowlie & C. Sills (Eds.), Relational transactional analysis: Principles in practice (pp. 279–286). London, England: Karnac Books. Chinnock, K. (2011a). Relational supervision. In H. Fowlie & C. Sills (Eds.), Relational transactional analysis: Principles in practice (pp. 293–303). London, England: Karnac Books.

Chinnock, K. (2011b). Relational transactional analysis supervision. Transactional Analysis Journal, 41, 336–350.

Clarkson, P. (1992). Transactional analysis psychotherapy: An integrated approach. London, England: Routledge.

Cochrane, H., & Newton, T. (2011). Supervision for coaches: A guide to thoughtful work. Chelmondiston, England: Supervision for Coaches Publishing.

Cornell, W. F., & Hargaden, H. (Eds.). (2005). From transactions to relations: The emergence of a relational tradition in transactional analysis. Chadlington, England: Haddon Press.

Hargaden, H., & Fenton, B. (2005). Analysis of nonverbal transactions drawing on theories of intersubjectivity. Transactional Analysis Journal, 35, 173–186.

Hargaden, H., & Sills, C. (2002). Transactional analysis: A relational perspective. Hove, England: Routledge. Hunt, J. (2011). Exploring the relational meaning of formula G in supervision and self-supervision. In H. Fowlie &

C. Sills (Eds.), Relational transactional analysis: Principles in practice (pp. 287–291). London, England: Karnac Books.

Mazzetti, M. (2007). Supervision in transactional analysis: An operational model. Transactional Analysis Journal, 37, 93–103.

Mazzetti, M. (2010). Analyzing the impact of prior psychotherapy on a patient’s script. Transactional Analysis Journal, 40, 23–31.

Mazzetti, M. (2012). On receiving the Eric Berne memorial award. The Script, 42(9), 9–11. Moiso, C. (1985). Ego states and transference. Transactional Analysis Journal, 15, 194–201.

Novellino, M. (1984). Self-analysis of countertransference in integrative TA. Transactional Analysis Journal, 14, 63–67.

Novellino, M. (1990). Unconscious communication and interpretation. Transactional Analysis Journal, 20, 168–172.

Novellino, M. (2003). Transactional psychoanalysis. Transactional Analysis Journal, 33, 223–230.

Novellino, M. (2012). The transactional analyst in action: Clinical seminars. London, England: Karnac Books.

Pierini, A. (2012). La supervisione come esperienza di crescita professionale e personale [Supervision as an experience of professional and personal growth]. Rivista Italiana di Analisi Transazionale, 32(25), 44–53.

Sills, C., & Mazzetti, M. (2009). The comparative script system: A tool for developing supervisors. Transactional Analysis Journal, 39, 305–314.

Tudor, K. (2002). Transactional analysis supervision or supervision analyzed transactionally? Transactional Analysis Journal, 32, 39–55.