Being There – Part 4

This post is a continuation of Marco Mazzetti’s article ‘Being There’. If you’re just joining us, you might want to start at Part One.

This post is a continuation of Marco Mazzetti’s article ‘Being There’. If you’re just joining us, you might want to start at Part One.

Why Do I Feel What I Am Feeling?

The second question helps us to move a step ahead. When my supervisor gently helped me to connect with myself by inquiring into the answer to this question, I discovered that I fell asleep with Edoardo because the way he spoke bored me since the content of his words did not connect to his inner realm. He was not speaking about himself but rather hiding, for reasons I did not yet understand.

Recognizing this led to a significant change in my perspective. I learned something new about myself: I feel bored when someone is talking to me in a superficial, inauthentic way. I realized that my sleepiness was not something shameful or reflective of a personal problem but something arising from the relationship. I moved from my internal dialogue to the relational field (Sills & Mazzetti, 2009). This is one of the moves we need to make in our development both as practitioners and supervisors. Often beginning trainees focus on their internal dialogue and are far from awareness of the transference-countertransference dynamics between them and their clients.

I distinguish between two types of emotional experience in supervision: those that belong to the area of countertransference and those that do not—or those that, even if stimulated by the patient, are not recognized by the practitioner as countertransference, as was the case with my feelings in relation to Edoardo (Mazzetti, 2007). In such instances, the phenomenon appears correlated to what Clarkson (1992) called ‘‘proactive countertransference’’ (p. 156). Even if the emotional result inside me was largely determined by my internal dialogue—in other words, it was a matter of transferential material—it occurred at that moment with Edoardo following his behavior. I wish to underscore here that the difference between countertransference and noncountertransference experiences basically has didactic value in helping us to understand what it is happening, even though the two phenomena largely overlap.

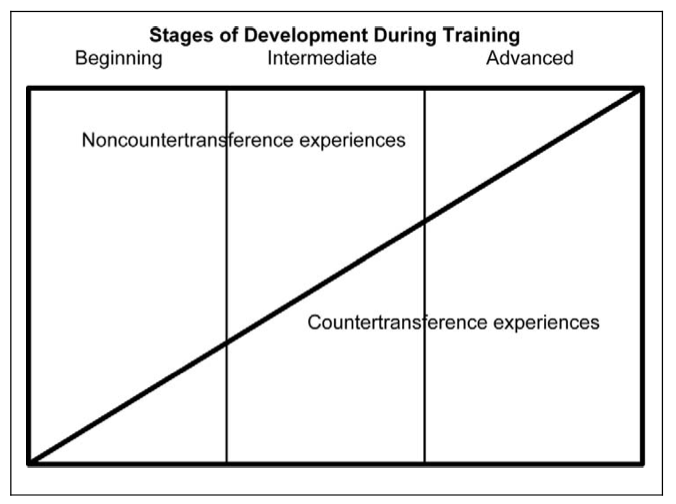

My observation is that the ratio of noncountertransference to countertransference experiences varies considerably during various stages of training. Figure 1 provides a representation of how during the earlier stages of training, noncountertransference experiences seem to prevail, whereas in advanced stages, awareness of countertransference is usually greater. I want to emphasize again that the difference lies in how the practitioner or supervisor experiences what is occurring. In other words, sometimes the professional is affected by something connected to the relational field with the client but does not experience it as the result of the relationship, just as I did not at first regarding my drowsiness with Edoardo. The answer to the question ‘‘Why do I feel what I am feeling?’’ helped me to understand what I discovered later in the work: that he had an unconscious need to keep me far away from him.

In another case, my inability to find a good answer to this question helped me to understand what was happening between me and Linda, a 30-year-old woman who came to my consulting room years ago. This second example also concerns a situation in which sexuality emerged in the therapy room. In my experience, these types of transference and countertransference dynamics are often avoided in supervision. However, my experience with Edoardo helped me to understand the dynamics between Linda and me.

During the initial sessions with Linda, I began to feel sexually attracted to her. You cannot imagine how much shame I felt about this; my blaming internal dialogue was unchained! Luckily, I had already had the experience with Edoardo and was thus not as far from understanding relational dynamics as I had been. So, I was able to begin more easily to address the issue in a professional way.

The answer to the question ‘‘What am I feeling?’’ was easy: sexual attraction. The second question was more difficult because it was not clear to me why I was feeling that way. Linda was a nice woman but not very sexy or attractive to me. I met other women every day who appeared more desirable to me without experiencing the same feeling of attraction I was feeling with Linda. Clearly there was something strange going on. I decided to stop any inner blaming and devote my energy to understanding what was happening.

As the therapy unfolded, I learned about several traumatic events in Linda’s life. She had suffered sexual harassment from her father when she was 12 or 13, when she was 19 she had had a romantic liaison with a priest whom she trusted, and later she had a love affair with a psychotherapist whom she saw 3 years before meeting me. We worked on these traumata. She came to understand what happened, found new meaning for these experiences, and began healing herself.

At the end of this analytic journey, I discovered that the sexual attraction I had felt had disappeared, and I then understood its significance. Often victims of violence are unconsciously searching for a repetition of the trauma in order to find a way to solve the traumatic effect of the violence. That is why psychotraumatologists consider the risk of a new violation to be higher in patients who have already suffered a similar traumatic experience. My understanding was that by sending hidden, unconscious messages, Linda was unconsciously searching to reenact with me the traumata she had suffered with significant males in her life (her father, the priest, and her prior psychotherapist) so that she could find a new way to solve her trouble. And to some extent, it happened, but we avoided reenacting the trauma. I acted in a different way and she was thus able to find a new meaning for her life story.

Since then, I have developed a particular sensitivity to this issue. I notice that feeling sexual attraction toward a patient can have a specific meaning, and often I have found stories of abuse in such cases.

Figure 1. Perception of Noncountertransference and Countertransference Experiences at Different Stages of Training (Mazzetti, 2007).

I want to underscore that such dynamics are the result of both the client and the practitioner and of the specific intersubjectivity between them. For example, Linda might have had the effect on me that she did because, among other possible reasons, I am a heterosexual male. It might have been different if I were homosexual or a female.