Being There – Part 1

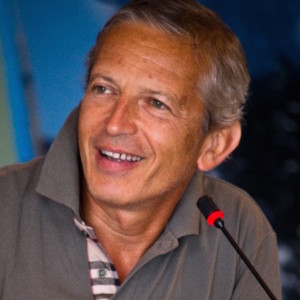

My colleague, Marco Mazetti, is a psychiatrist, Transactional Analyst and a lecturer at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Brescia, Italy. He founded, and runs, the Milan Institute for Transactional Analysis. Together we served on the Transactional Analysis World Council of Standards (TAWCS) and Marco is a brilliant and leading figure in the industry.

My colleague, Marco Mazetti, is a psychiatrist, Transactional Analyst and a lecturer at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Brescia, Italy. He founded, and runs, the Milan Institute for Transactional Analysis. Together we served on the Transactional Analysis World Council of Standards (TAWCS) and Marco is a brilliant and leading figure in the industry.

Marco has kindly given me permission to share the following article, which he wrote in response to receiving the 2012 Eric Berne Memorial Award for his work on supervision. This article will be useful for anyone interested in the theory underpinning supervision, and provides a practical approach to the analysis of the relational dynamics in both supervision and clinical practice through three questions practitioners might ask themselves: What am I feeling during the session? Why do I feel what I am feeling? Why does the other person want (unconsciously) me to feel what I am feeling?

Being There: Plunging Into Relationship in Transactional Analysis Supervision (On Receiving the Eric Berne Memorial Award)

Marco Mazzetti

Abstract

This article was written in response to receiving the 2012 Eric Berne Memorial Award for the author’s work on supervision. It underscores the value of theoretical knowledge of supervision for all practitioners, even those not directly involved in offering supervision. It also provides a practical approach to the analysis of the relational dynamics in both supervision and clinical practice through three questions practitioners might ask themselves: What am I feeling during the session? Why do I feel what I am feeling? Why does the other person want (unconsciously) me to feel what I am feeling? The use of these questions is described and illustrated through two case studies.

Keywords

supervision, self-supervision, transference, countertransference, relational transactional analysis, relational process, relational field

Generally Speaking

I was immensely pleased and honored to receive the 2012 Eric Berne Memorial Award (EBMA), which I accepted at the ITAA-SAATA (South Asian Association of Transactional Analysts) Conference in Chennai, India, on 10 August 2012. As I said at the time, it means a great deal to me because of the important role Berne and transactional analysis have played in my personal and professional development. I owe thanks to many people who helped me along the way as I grew as both a person and a transactional analyst and as I developed the ideas on supervision for which I was given the award (Mazzetti, 2007).

I wish here to strongly reaffirm my gratitude to these friends and colleagues. However, rather than repeat those thanks, as important as they are (and that were summarized in Mazzetti, 2012), I want to take this opportunity to expand some of my recent ideas about supervision. Doing so departs a bit from what these EBMA articles are usually about, but what I write here reflects a logical outgrowth of my EBMA work as I have continued to think about and develop my ideas on supervision.

Generally speaking, supervision is considered a matter for trainers. However, if knowing about the theory and operational methods of supervision in transactional analysis were to concern only teachers and supervisors, even though their number is expanding (due to the worldwide success of transactional analysis), there probably would not be much sense in reflecting on and devoting energies to the dissemination of so much knowledge on this subject.

I hold a different view, which is that supervision concerns all professionals who use transactional analysis. Of course it concerns trainers, but not only those who do training, because ethical professionals (and the emphasis on ethics is something transactional analysis is proud of) devote a good deal of time and energy to thinking about their work and reflecting on their cases: in a nutshell, doing self-supervision. Just as the philosophy of transactional analysis in the clinical field involves facilitating the growth of patients toward autonomy by offering them the tools to become ‘‘analysts of themselves,’’ likewise, I think one of the goals of a trainer is to help trainees to become effective supervisors of themselves.

Transparent thinking, ‘‘putting one’s cards on the table,’’ and explaining why one stance is preferable to another are tools that supervisors offer to trainees, alongside, of course, advice, reflection, and support. This becomes a model for learning how to reflect on one’s professional activity. I think that self-supervision is something that professionals need, and I would go so far as to say that when we work as transactional analysts, in a certain way, we are all supervisors.

If we accept this perspective, supervision is of interest to us all. Being able to recognize and understand a parallel process is useful to everyone, not just trainers and trainees, as are identifying the critical moment in a therapeutic relationship, picking up signals of danger and the need of both patient and therapist for protection, decoding transference and countertransference processes, and being able to identify possible directions for development.

Becoming a good self-supervisor, however, is different from becoming self-centered, thinking of oneself as all knowing, and not being open to other points of view. Being in supervision enriches professionals throughout their professional lives, and I strongly support the idea that it is beneficial even for expert professionals who are trainers. From this standpoint, knowing more about the theory of supervision can help professionals enjoy the benefits of supervision even more.

The reflections I am presenting here were initially prompted, as often happens, by my own personal experience. I had perceived that I was achieving advances in my psychotherapeutic practice at the very moment I started working as a supervisor. Paying attention to processes, capturing key issues, and seeing strategic directions and possible dangers are skills that I have refined by studying supervision and practicing it with trainees, and they are all things that have significantly enriched my work with patients. Moreover, knowing about the theory and practice of supervision is beneficial to me when I am supervised because it helps me to understand and efficiently use the stimuli I receive during that process.

However, beyond my personal use of the tools of supervision for self-supervision, I have several colleagues who do not consider themselves to be supervisors and trainers in the strict sense but are at times called on for help by professionals from other fields. The counsel they provide usually has the connotation of supervision, for instance, in working with school teachers or teams of educators or offering consultations in the legal field. It may be useful for these professionals to know what supervision is about and its underlying theoretical and technical parameters. In fact, the most common reaction among colleagues who are beginning their training as supervisors is surprise. They discover that doing supervision is quite different from doing therapy and other professional activities. It is another profession, with its own rules and parameters that need to be understood and acquired. Knowing these parameters is a way of protecting one’s professionalism when occasionally we are put in the position of doing supervision in less familiar settings.

Briefly, self-supervision as supervision is for everyone and so, consequently, is theory about supervision. One of the most useful things that a supervisor can do is model the process of reflection, including inquiring into the supervisee’s experience, which helps the person to develop the ability to reflect on his or her experience in depth.