Supervision in Transactional Analysis – Part 9

This post is a continuation of Marco Mazzetti’s article on ‘Supervision in Transactional Analysis’. If you’re just joining us, you might want to start at Part One.

This post is a continuation of Marco Mazzetti’s article on ‘Supervision in Transactional Analysis’. If you’re just joining us, you might want to start at Part One.

Conclusions

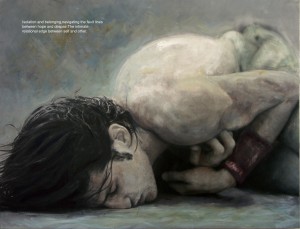

Transactional analysis supervision has its own distinguishing features. Even though contributions from other theories have been integrated into TA, transactional analysts interpret such phenomena in unique ways. Of the seven points in the model described in this article, there are some that are typically transactional analysis (e.g., contracting and OKness). Although others may appear to be less specific to transactional analysis (e.g., parallel process from the psychoanalytic world), they have become soundly integrated into transactional analysis theory and practice. In addition, the focus in transactional analysis on ethics gives special meaning to the subject of key issues and to the need for protection, and the discount matrix gives specific direction to the search for key issues. We are, therefore, entitled to think of a transactional analysis theory of supervision, one that is intimately linked to practice.

According to Eric Berne, transactional analysis in psychotherapy was a means for treating people; it had no other justification. It was a theory for practice, because he always profoundly felt he was a “doctor,” someone whose purpose in life was to treat people in order to cure them, not to interpret, to gain knowledge, to explore, or to work out smart theories. His last work—a kind of spiritual legacy—was a lecture he gave on 20 June 1970 (a week before the heart attack that was to kill him on July 15) at the conference of the Golden Gate Group Psychotherapy Society. He forcefully and firmly emphasized the healing mission of psychotherapists when he said, “There’s only one paper to write which is called ‘How To Cure Patients’ ” (Berne, 1971, p. 12). Steiner (1974/ 1990), in the pages devoted to Eric Berne in his book Scripts People Live, writes that Berne had this same approach during his supervision workshops:

During meetings, and in general, he allowed no mystifications, no hierarchical or professional pomposity—or “jazz” as he was apt to call it. When in presence of such mystifying behavior he would listen patiently; then, biting on his pipe and arching his eyebrows, say something like, “This is well and good; all I know is that the patient is not getting cured. (p. 15)

In developing the model described in this article, my aim was to follow Berne’s lesson: no theory is worthwhile if it is not anchored to practice, to the goal of treating or effectively supervising people. I have always appreciated this practice-anchored approach of transactional analysis. It is one of the reasons I became a transactional analyst, and after many years, I am still happy I made that decision.

Transactional analysis offers a specific theory of supervision, one designed to protect and take care of trainees, and through them, their clients. My personal hope is that additional contributions will come from other colleagues to help further develop a specific transactional analysis theory of supervision and thereby to strongly support our effective and broad practice.

Marco Mazzetti, M.D., is a psychiatrist and a member of the European Association of Transactional Analysis (EATA) and the ITAA. He is a Teaching and Supervising Transactional Analyst (psychotherapy) and a university lecturer. Marco carries out his clinical, research, and training activity at the Ethno Psychiatry Service “Terrenuove” and at the Centro di Psicologia e Analisi Transazionale of Milan, Italy. He can be reached at Centro di Psicologia e Analisi Transazionale, Via Archimede, 127, 20129 Milano, Italy; e-mail: marcomazzetti.at@libero.it .

REFERENCES

Allen, J. R., & Allen, B. A. (2005). The therapeutic contract. In J. R. Allen & B. A. Allen, Therapeutic journey: Practice and life (pp. 55-58). Oakland, California: TA Press.

Berne, E. (1957). Intuition V: The ego image. Psychiatric Quarterly, 31, 611-627.

Berne, E. (1994). Principles of group treatment. Menlo Park, CA: Shea Books. (Original work published 1966) Berne, E. (1971). Away from a theory of the impact of interpersonal interaction on non-verbal participation. Transactional Analysis Journal, 1(1), 6-13.

Cassoni, E. (2004). Il processo parallelo tra supervisione e terapia, Occasione di reciprocità [Parallel process between supervision and therapy: An opportunity for reciprocity]. Quaderni di Psicologia, Analisi Transazionale e Scienze Umane, 42, 99-116.

Cassoni, E. (2007). Parallel process in supervision and therapy: An opportunity for reciprocity. Transactional Analysis Journal, 37, 130-139.

Cheney, W. D. (1971). Eric Berne: Biographical sketch. Transactional Analysis Journal, 1(1), 14-22.

Clarkson, P. (1992). Transactional analysis psychotherapy: An integrated approach. London: Routledge. English, F. (1969). Episcript and the “hot-potato” game.

Transactional Analysis Bulletin, 8(32), 77-82. Erskine, R. G. (1982). Supervision for psychotherapy: Models for professional development. Transactional Analysis Journal, 12, 314-321.

European Association for Transactional Analysis Professional Training and Standards Committee. (2003, July). TSTA examination, supervision segment [Form]. In EATA training and examinations handbook (Section 12.11.8). Retrieved 30 April 2007 from http://www. eatanews.org/index.php?option=com_docman&task= cat_view&gid=30&Itemid=206 .

Goulding, M. M., & Goulding, R. L. (1979). Changing lives through redecision therapy. New York: Brunner/ Mazel.

Holloway, M. M., & Holloway, W. H. (1973). The contract setting process. In M. M. Holloway & W. H. Holloway, The monograph series: Numbers I-X (No. 7). Medina, OH: Midwest Institute for Human Understanding.

Lai, G. (2004). La supervisione immateriale [The immaterial supervision]. Quaderni di Psicologia, Analisi Transazionale e Scienze Umane, 42, 45-70.

Macefield, R., & Mellor, K. (2006). Awareness and discounting: New tools for take/option-oriented settings. Transactional Analysis Journal, 36, 44-58.

Rotondo, A. (1986). La contrattualità in analisi transazionale [Contracting in transactional analysis]. Neopsiche, 4(8), 4-8.

Rotondo, A. (2003, 22 November). La costruzione del contratto [The building of a contract]. Presentation at CPAT-SIMPAT Conference, Milan, Italy.

Schiff, J. L., with Schiff, A. W., Mellor, K., Schiff, E., Schiff, S., Richman, D., Fishman, J., Wolz, L., Fishman, C., & Momb, D. (1975). Cathexis reader: Transactional analysis treatment of psychosis. New York: Harper & Row.

Steiner, C. M. (1971). The stroke economy. Transactional Analysis Journal, 1(3), 9-15.

Steiner, C. M. (1990). Scripts people live: Transactional analysis of life scripts. New York: Grove Press. (Original work published 1974)

Stewart, I., & Joines, V. (1987). TA today: A new introduction to transactional analysis. Nottingham, England, and Chapel Hill, NC: Lifespace Publishing.

Tudor, K. (2002). Transactional analysis supervision or supervision analyzed transactionally? Transactional Analysis Journal, 32, 39-55.