Supervision in Transactional Analysis – Part 8

This post is a continuation of Marco Mazzetti’s article on ‘Supervision in Transactional Analysis’. If you’re just joining us, you might want to start at Part One.

This post is a continuation of Marco Mazzetti’s article on ‘Supervision in Transactional Analysis’. If you’re just joining us, you might want to start at Part One.

Develop an Equal Relationship

The primary value on which transactional analysis was founded is that each person is OK. Marguerite Yourcenair’s (source unknown) words are effective in giving sense to what it means to have respect for the other’s OKness: “Respect is the sense of freedom of others, of the dignity of others, it is acceptance of a being as he is, without delusions but also without the slightest hostility or the slightest contempt.”

In supervision this means that we need to accurately distinguish between what the other “is” and what the other “does.” In transactional analysis we distinguish between unconditional strokes addressed to “being” and conditional strokes addressed to “doing.” In supervision, at times we need to give negative conditional recognition to trainees. It may be worthwhile to bear in mind that refraining from giving conditional negative strokes, when it is appropriate, is a way of discounting trainees’ OKness and their ability to accept confrontations that will be useful for their professional growth.

An equal relationship is also fundamental in modeling the process. The neurosciences remind us that learning is effective when it occurs at two levels: unaware (implicit memory) in the limbic lobe (as in the case of modeling) and consciously at the level of the cortex. Clarkson (1992) pointed out, “As we know from Berne’s third rule of communication, the outcome of any transaction is determined at the ulterior or psychological level. Therefore, the most effective way of supervising is through modelling the desirable process” (p. 276).

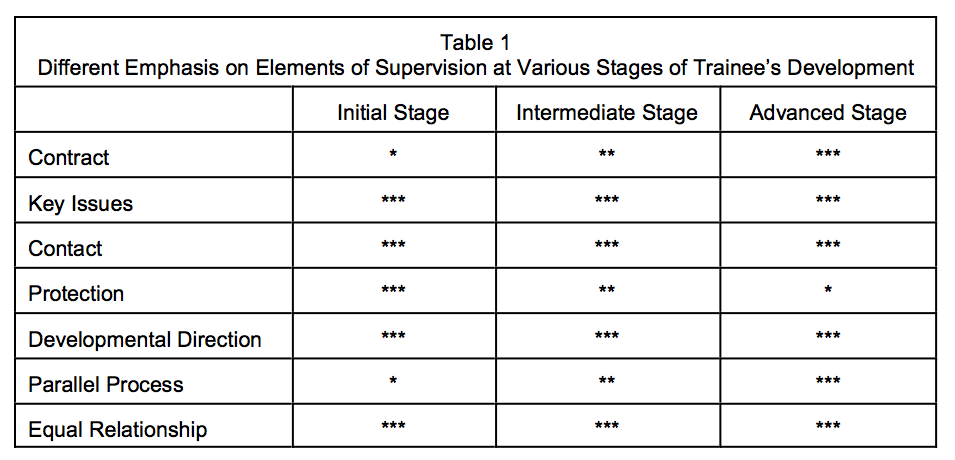

The Operational Model and Trainees’ Development Stages

There are different ways of applying the seven elements of supervision to the three stages in a trainee’s development. Even though I have had limited experience in counseling, with organizations, and in education, I think these remarks most likely also hold for the other fields of transactional analysis application. The different ways of applying these elements are qualitative, such that the way in which one deals with the issue depends on whether the trainee is a beginner or an expert. There is also a quantitative difference. While attention is continually focused on some elements (e.g., equal relationship), the amount of focus on other elements (e.g., parallel process) varies. Table 1 summarizes the different emphasis I attribute to the elements of supervision in the three stages of a trainee’s development.

All seven points must be present in any supervision. The fact that with advanced trainees there is only one asterisk on protection does not mean that the supervisor is exempt from paying attention to protection issues. The supervisor must pay attention to each of these points at all times. Table 1 merely expresses the fact that, in my experience, I frequently find myself saying to a trainee in the initial stage, “Be careful, there is this risk for this client; make sure you provide the necessary protection.” Or I might say, “There could be a danger for you with this client and the danger I see is this.” In contrast, this happens rarely with advanced trainees. Similarly, I generally explore parallel process more frequently and extensively with advanced trainees, but this does not mean I ignore parallel process with trainees in the initial stage. In fact, I think one needs to be aware of parallel process at all times, even though it may be preferable to choose intervention strategies centered on other aspects of the tools of supervision.