Supervision in Transactional Analysis – Part 7

This post is a continuation of Marco Mazzetti’s article on ‘Supervision in Transactional Analysis’. If you’re just joining us, you might want to start at Part One.

This post is a continuation of Marco Mazzetti’s article on ‘Supervision in Transactional Analysis’. If you’re just joining us, you might want to start at Part One.

Increase Developmental Directions

Clarkson (1992) wrote:

Because supervision is intrinsically a method for continuing learning and growth throughout anybody’s professional career (no matter how senior or experienced they may be), it is assumed that there will always be potential for further growth and development. . . . However, we consider it the supervisor’s responsibility to offer challenges, direction or support for extending the trainee’s horizons. (p. 276)

This concept can be interpreted very broadly.

“Developmental directions” may refer to new options for intervention in a particular case as well as to discoveries made during supervision. It can also mean understanding how to stimulate trainees’ cultural growth and their longterm professional passion. Both these dimensions should be kept in mind.

The supervisor checks that the contract has been fulfilled and that directions for growth have been identified. This is a way of keeping the process explicit and clear and avoiding the risk of misunderstandings. When ending a supervision session, many colleagues openly review the new options that the trainee has identified, linking them explicitly to the contract. For example: “And so, you have understood why you felt angry at your client during your last session. How can this be useful in working with him?”

Trainees’ long-term growth can be facilitated by offering bibliographic references on the issue that was discussed or on related issues that can expand the trainee’s knowledge and skills. We can also encourage trainees’ professional passion by inviting them to become aware of the positive motivations that drive them to continue their growth process, asking them what they liked and what they got out of the supervision and “stroking” the pleasant feelings (joy, hope) that they communicate.

When supervision is part of an ongoing training program, the direction for growth can be identified through long-term contracts, that is, “training contracts” that are similar to “therapy contracts.” Discussion of these contracts—for instance, at the beginning of the training year in training groups and at regular intervals in between— offer opportunities for pinpointing and agreeing on the developmental direction. Follow-up will show whether these contracts are being fulfilled and will relate them to the results of each supervision session.

Throughout trainees’ various developmental levels of training, the key issues identified will change, as will the contract strategies and emotional aspects. Each trainee, whether he or she is at a beginner, intermediate, or advanced stage, needs the supervision to end with developmental prospects for the specific case and longterm growth directions to follow.

Increase Awareness and Effective Use of Parallel Process

In her checklist, Clarkson (1992) speaks to how the supervisor models the process. Modeling the process is a vast concept that begins during the contract discussion (point 1), continues through “emotional contact with the trainee” (point 3), and concludes in the ability to maintain an “I’m OK, You’re OK” relationship (point 7). Paying attention to parallel process, in Clarkson’s view, is part of the modeling process. I prefer to dedicate a specific point in the list to parallel process, which, in my view, deserves special attention because it is such a powerful tool in psychotherapy.

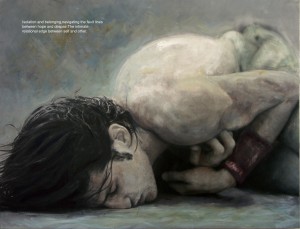

Cassoni (2004, 2007) offers an interpretation of parallel process from the perspective of neuroscience and points out that parallel process may be viewed as a condition in which the mental states of the client-therapist and/or the therapist-supervisor are aligned. This alignment often leads to an affective attunement of the therapist with his or her client. If we take this perspective to its extreme, we might say that parallel process in supervision—that is, the therapist acts with the supervisor as his or her client acts with him or her—is the expression of a deep knowledge or understanding of the client. In other words, to act like his or her client, the therapist must have had a deep and thorough understanding of that person. Of course, this is a sui generis, emotional and unconscious understanding, but it is nevertheless profound. Parallel process is, therefore, the expression of accurate, deep, and unconscious knowledge. Bringing this phenomenon into the trainee’s awareness offers him or her a formidable instrument for understanding the client.

In my supervision practice, I use parallel process differently depending on the trainee’s level of experience. With beginners, I identify the parallel process even though in most cases I refrain from using it. At this stage, trainees have other priorities: They are intent on identifying the key issues of the clinical problem and on ensuring adequate protection for themselves and their clients. I limit myself to pointing out parallel process when it emerges in a conspicuous manner so that the trainee can start becoming familiar with the concept and considering it as a possible ally.

With intermediate trainees, I use the concept of parallel process more directly. I bring parallel process dynamics into the realm of awareness and make comparisons between how we solve them in supervision and how they can similarly be managed in therapy. I also use the idea of parallel process to refine trainees’ empathic skills and to help them recognize the phenomenological expression of their clients’ experiences.

In the advanced stage—particularly when trainees are training as Provisional Teaching and Supervising Transactional Analysts—I concentrate on subtle aspects that often show up as cotransference dynamics (i.e., common to the therapist and client) or countertransference dynamics that offer insight, guidance for the therapy, food for thought, and input for self analysis for the therapist.