Supervision in Transactional Analysis – Part 5

This post is a continuation of Marco Mazzettis’ article on ‘Supervision in Transactional Analysis’. If you’re just joining us, you might want to start at Part One.

This post is a continuation of Marco Mazzettis’ article on ‘Supervision in Transactional Analysis’. If you’re just joining us, you might want to start at Part One.

Erroneously, I had thought that therapy was the place in which emotions were taken care of and that there was no room for them in supervision. Today my views are different. I think that empathy and the ability to attune to the trainee’s emotional experiences are skills that the supervisor needs. In fact, good emotional contact is a precondition for good supervision. Emotions are part of the supervision: It is necessary to recognize them, name them, and understand them in order to develop effective awareness, even though the aim is not to change the trainee’s script as is done in therapy. Supervision may, however, reveal issues that need to be dealt with in therapy. Emotional issues experienced in supervision may trigger insights and have strong transformational efficacy, especially with advanced trainees who have greater self-awareness. In fact, Lai (2004) openly discussed the therapeutic function of supervision.

For my part, I make a distinction between two types of emotional experiences in supervision: those that belong to the area of countertransference and those that do not. Noncountertransference experiences have to do mainly with the trainee’s internal dialogue: emotions that he or she may (or may not) express as transference experiences with the supervisor. In other words, noncountertransference emotions are experienced by therapists on the basis of their own experience of life, personal history, script, and so on, not as a response to their clients’ stimuli, while countertransference emotions are “all the conscious and unconscious feelings and thoughts of the therapist” (Lai, 2004, p. 49) toward his or her clients.

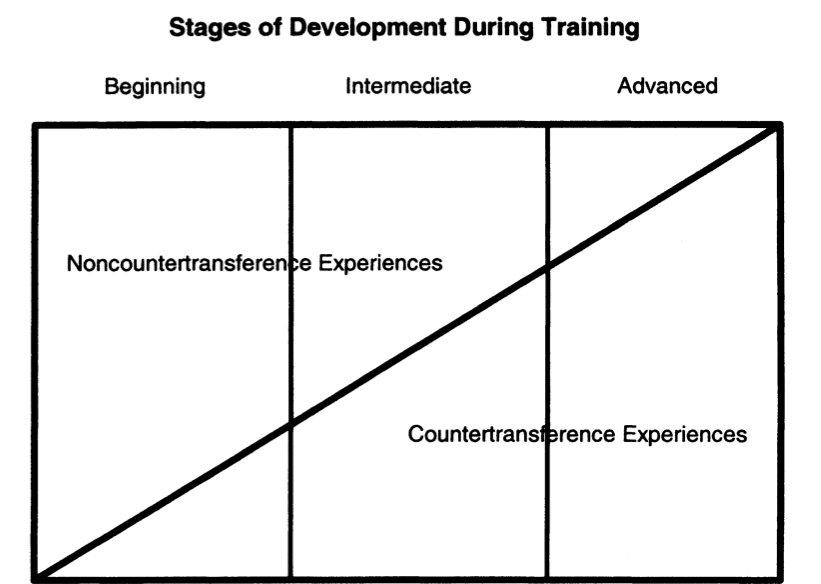

This distinction is useful because, in my experience, the ratio of noncountertransference and countertransference experiences varies considerably in the various stages of training (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Prevalence of Noncountertransference and Countertransference Experiences at Various Stages of Training

Figure 2 provides a graphic representation of how during the earlier stages of training, noncountertransference experiences prevail. Trainees are just beginning to grapple with a new role that they need to know well, and they may feel they are not up to the task. Supervisors are seen as authority figures and as such may trigger transference reactions. Taking care of these experiences is part of the supervisor’s task. Creating a positive stroke economy (Steiner, 1971) in the supervision setting is fundamental. This is the stage at which trainees most need positive conditional strokes centered on their skills so that they can know their strengths and on which they can build their skills. Erskine (1982) suggests temporarily ignoring what the trainee does not do well so as to reduce any feelings of inadequacy and to support self esteem. I agree, provided this does not cause harm to the trainee or clients. Any transference with the supervisor must be openly dealt with and discussed. In this stage it is not worthwhile dwelling on countertransference experiences because the trainee has other primary needs. W hen countertransference dynamics do emerge, it may suffice to acknowledge and legitimize them, provided they are not linked to obvious therapeutic problems.

In the intermediate stage, while noncountertransference experiences tend to decrease and to be well managed, countertransference experiences become increasingly important. This is the level at which they are to be given considerable time in supervision. In this stage the essential strategy is to help trainees become aware of countertransference experiences and to legitimize the feelings prompted by their clients. For example, it is legitimate to have feelings of irritation, boredom, or sexual arousal in the presence of clients. It may be useful to remind trainees that moral judgments are applied to behavior, not to feelings, and that accepting all of one’s feelings means becoming master of a precious diagnostic instrument. In this stage, personal therapy will be of particular value for trainees because it provides the opportunity for dealing with issues that interfere with the efficacy of their work with clients. In the advanced stage, emotional contact with trainees will focus above all on countertransference experiences.

Using empathy to understand trainees’ countertransferential experiences helps them to recognize the richness of such experiences and introduces them to the ways these experiences can serve as a powerful instrument for understanding others. In fact, transactional analysis came into being because Berne used something that today we would consider a countertransferential phenomenon. When discussing the idea of the “image of the ego” (which predates the concept of ego state), Berne (1957) said, with regard to his lawyer patient, that he felt like he was facing a three-year-old throbbing with embarrassment. He was speaking about a full-blown countertransference experience. When we use social diagnosis in the therapeutic setting— being aware of which ego states are prompted by our clients—or when we feel we are hooked in a game or invited into a symbiosis, we are reading the territories of countertransference with the instruments of transactional analysis.

It is worth remembering that noncountertransference experiences may continue to hover in the supervision setting. For instance, when certification exams draw closer, it is not uncommon for the old survival conclusions of a trainee’s script to emerge. Issues related to being successful, to finishing things, to being examined, or to facing authority can be expressed through transference with the supervisor. Being aware of these dynamics and paying attention to them may be decisive in helping the trainee recognize and overcome such obstacles. Furthermore, observations in the neurosciences demonstrate that the ability to create delicate, careful empathic contact in the supervision relationship effectively models the relationship process and promotes implicit learning in the trainee.