The Comparative Script System – Part 1

When working as a supervisor, having an understanding of the comparative scripts can enhance your work. In this article, the authors explore comparative scripts and look at how the Supervisee, the Supervisor and the client may have interlocking scripts and how to work with it.

When working as a supervisor, having an understanding of the comparative scripts can enhance your work. In this article, the authors explore comparative scripts and look at how the Supervisee, the Supervisor and the client may have interlocking scripts and how to work with it.

If you would like to read more about supervision and theory, I’ve previously shared Charlotte and Marco’s writing on ‘Being There: Plunging Into Relationship in Transactional Analysis Supervision’ and ‘Supervision in Transactional Analysis: An Operational Model’.

The Comparative Script System: A Tool for Developing Supervisors

AUTHORS: Charlotte Sills and Marco Mazzetti

Abstract

The aim of this article is to offer to transactional analysts a simple theoretical and practical tool to support relational supervision. The authors propose the comparative script system as a useful aid to the training of supervisors, with particular reference to three areas: a framework for focusing on the key issues in supervision; a practical instrument for understanding and visually representing transference-countertransference dynamics; and a clarification of the boundary between supervision and therapy. While the focus is on its use in psychotherapy, the model can be used in all fields.The comparative script system (Sills & Salters, 1991) was originally designed for integrating the various “schools” of transactional analysis in order to enrich diagnosis and treatment planning in therapy. It was also suggested as a framework for reflection and self-supervision. Subsequently, it was developed as both a framework and a procedural strategy for integration in psychotherapy (Lapworth, Sills, & Fish, 2001).

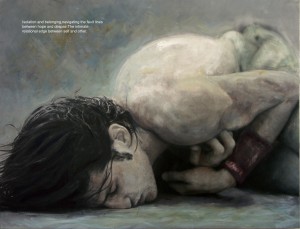

In this article, we briefly describe the comparative script system and introduce it as a supervision tool in three challenging areas. First, supervisors are often required to help therapists manage a mass of information about the client, the situation, and the interaction in the consulting room. Therapists often find it difficult to organize this data, as well as their thoughts and feelings, in such a way as to formulate the key issues. The comparative script system offers a framework that describes the two arcs of past and present time and internal and external experience. Second, in relation to transferential and countertransferential dynamics, supervisors in training often complain that there is no clear way to describe the cocreated relationship such that theory is pragmatically linked to practice yet remains dynamic.

In our view, the comparative script system can offer an effective theoretical and practical support for portraying this relational field between practitioner and client. Third, another common issue with beginning supervisors is defining the parameters of the supervisory field: what is “permitted” and what is not during supervision sessions? Often they ask themselves if it is appropriate to address a supervisee’s personal material or if this is an area that belongs only in therapy. Can the supervisor openly name and even challenge the professional’s script issues when they emerge as a result of the therapeutic work? We think that an important issue in training supervisors is to define a clear boundary between supervision and therapy. We are aware that supervision can have (and often does have) a therapeutic effect for the supervisee, but this is not the goal of supervision and should not be pursued by the supervisor.

The supervisor’s responsibilities include helping to identify and raise awareness of how the therapist’s personal patterns may be affecting and affected by the therapy, with the goal of improving service to the client and developing the supervisee’s skills and understanding. However, it is not the role of the supervisor to address script issues directly in order to promote changes at the script level. In our practices, we support clearly differentiating between the supervision setting and the therapeutic one, including avoiding the dual relationship of acting as both supervisor and therapist—even in different settings—with the same person. This boundary clarity promotes professionalism and protects supervisees from the potential harm arising from a relationship that attempts to be therapeutic and yet also normative, educative, and evaluative.

At the same time, we think that feelings, sensations, and irrational responses are certainly a matter for supervision and a rich source of information for the therapist, both about the therapeutic relationship and the client’s world. Awareness of internal experiences during the professional work of transactional analysts (regardless of the different fields of application) is crucial. The comparative script system offers a way to identify clearly a boundary between what pertains to the relational field of practice and the possible connections to old script issues, which are the domain of therapy.