Being There – Part 3

This post is a continuation of Marco Mazzetti’s article ‘Being There’. If you’re just joining us, you might want to start at Part One.

This post is a continuation of Marco Mazzetti’s article ‘Being There’. If you’re just joining us, you might want to start at Part One.

What Am I Feeling?

The first question is focused on countertransference. The characteristics of countertransference have already been described in the transactional analysis literature (e.g., Hargaden & Sills, 2002; Novellino, 1984, 2012). I wish to describe here some steps that practitioners and supervisors can use to deal with it.

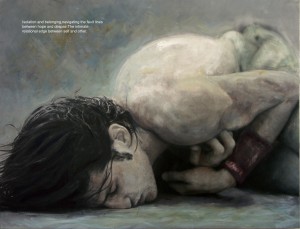

Probably, the main step is to have a countertransference. This sentence might look odd (and probably stupid) to experienced colleagues. To the extent that we acknowledge the existence of unconscious communication, we obviously admit that we always have some kind of countertransference! I personally share this admission. Thus, when I say ‘‘have countertransference,’’ I mean being aware of it, allowing ourselves to have and discover it. Sometimes, however, less experienced practitioners and supervisors do not hold in their minds that countertransference is a faithful and constant companion on the journey of our profession. Indeed, it is a powerful instrument for the relational transactional analysis supervisor.

I offer an example from my own experience as a therapist, one that shows the difficulty of having a countertransference. When I was much younger, I met 24-year-old Edoardo, who sought me out for psychotherapy. After a dozen sessions with him, the therapy became increasingly difficult for me because as soon as our session began, I felt so sleepy that I could hardly keep my eyes open. I tried many experiments to overcome the problem: I moved the time from 2 p.m. to later, suspecting my post-lunch digestion to be the cause of such drowsiness; then I began drinking a cup of coffee just before meeting him; later it became a double cup of coffee. When none of that worked, I decided to take a half-hour break before his appointment, during which I took a walk (along with, of course, the double cup of coffee) to try and wake up. All of this was totally without success. As soon as Edoardo started to talk, I was falling asleep again. My perception was that I did not have a countertransference, I was simply asleep. I felt so guilty, blaming myself for being so unserious, not engaged with the job, unable to pay the right attention to a suffering man who was coming to be treated by me . . . who was falling asleep! Shame on me!

Eventually, I brought up the case in supervision, and surprisingly, I discovered that my yawns in Edoardo’s presence were not a sign of rudeness but signals about something that was happening in our relationship. I came to understood that his monotonous talk had been like having a smoke screen between the two of us in order to hide the real issues inside him. He was afraid to be in contact with his suspected and unaccepted homosexuality, including, perhaps, any possible sexual attraction between us (I was slightly older than he was) or some prejudice I might have about homosexuality (homophobia in my culture was quite widespread at that time, especially among young men). He was hiding his feeling of being wrong and bad with his monotone and superficial words. It was a great discovery for me. Since then, I have thought that for me, yawns are useful signifiers instead of signs of a failure of professionalism.

In my experience as a trainer, the awareness of countertransference emotions (and the internal permission to have them) is not common among trainees and supervisees. And because we transactional analysts are such nice people, some emotions seem more difficult for us to accept in ourselves, such as being bored, irritated, or angry with a patient or, worse still, feeling sexual attraction toward one. If we allow ourselves to respond freely to the question ‘‘What am I feeling in the presence of this client (or supervisee)?’’ we quickly discover what a powerful tool we have in our countertransference.